The Tiny Episodes Making Big Waves

Microdramas, a form of serialized short video entertainment with episodes usually lasting between one and five minutes, have rapidly evolved from a niche phenomenon in China to a global force in the media landscape. Often compared to a blend of soap operas and TikTok videos, microdramas are reshaping the way audiences consume content, the way platforms monetize entertainment, and the way creators experiment with storytelling.

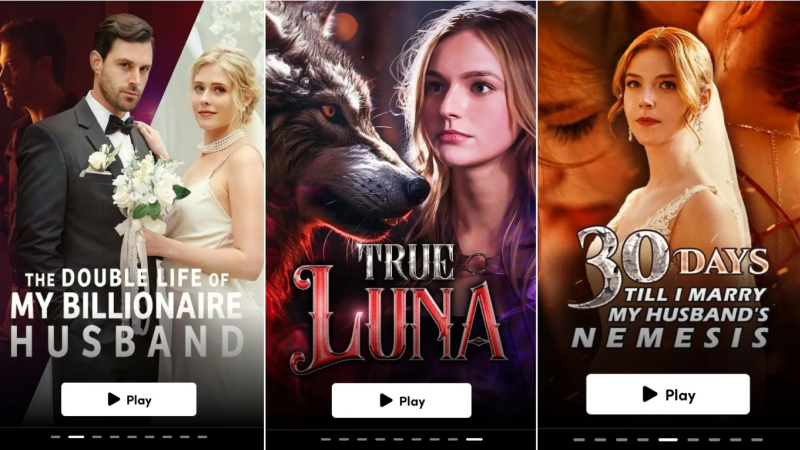

The genre originated in China in the early 2020s, largely as a response to shifting audience habits and the dominance of short video apps like Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok). Production companies quickly realized that viewers were hungry for fast-paced, emotionally charged, and easy-to-digest content. Microdramas capitalized on this by offering bingeable stories that could be consumed during short breaks throughout the day. The format also proved to be highly addictive, often relying on cliffhangers and melodramatic plots to keep audiences hooked. Apps such as ReelShort and DramaBox emerged as key players.

Monetization strategies also distinguish the format from traditional subscriptions. Most platforms adopt a freemium model, where the first episodes are free and later episodes are locked behind in-app purchases with coins or credits. Others rely on advertising or hybrid models, allowing users to remove ads with a one-time payment per title or per month. This gamified approach monetizes attention in new ways, proving particularly effective with mobile-native audiences.

In China, the boom was almost immediate. The country’s well-established mobile entertainment ecosystem created fertile ground for microdramas to flourish. By 2023, microdrama apps were pulling in hundreds of millions of users, generating substantial revenues through subscription models, ad sales, and pay-per-episode options. According to a recent report by Media Partners Asia (MPA), the microdrama market outside China is projected to top $9 billion in the coming years while the global figure including China could exceed $20 billion, underlining the genre’s explosive growth potential. In details: revenues in China for micro-dramas have climbed from $0.5B in 2021 to $7B in 2024 and are expected to exceed $16.2B by 2030, with a 11.5% compound annual growth rate (CAGR).

By 2030, advertising will contribute 56% of revenues, with subscriptions at 39% and commerce at 5%. Outside of China, the global microdrama market generated $1.4B in 2024 and is forecast to reach $9.5B by 2030, with a 28.4% CAGR. In China, micro-dramas have become “mainstream,” with revenues set to exceed $9.4B in 2025, with more than 830 million viewers consuming microdramas. From this audience, nearly 60% pay or transact.

The Chinese microdrama market is also entering a new phase with the rise of premium micro-dramas, carrying budgets of $400.00 to 600.000 each, and with franchise potential. Artificial intelligence has already been integrated across the value chain, from personalized discovery, faster iteration, and genre testing, to branching storylines and viral loops.

Investment in microdramas is surging. Variety reported that global spending on microdramas exceeded $10 billion in 2024 and is forecast to rise sharply, with more than $20 billion projected within three years as Western and Asian companies compete for market share. This includes not only content production but also technological infrastructure, such as the recommendation algorithms that drive user engagement. According to Appfigures, ReelShort saw revenues of over $25 million in December 2024 alone, largely from in-app purchases and subscriptions, while DramaBox followed closely behind with double-digit monthly revenue growth. Appfigures counts 215 micro-drama apps on the U.S. stores, and May 2025 consumer spend topped US $100 million. Sensor Tower adds that the three largest apps now post ARPDAU figures that rival mid-tier casual games. These figures underscore the commercial viability of microdramas and their capacity to rival traditional streaming platforms in audience reach.

A season of sixty one-minute episodes typically costs from RMB 200–300 K (≈ US $27–41 K) shoot in China, or around $200K shoot in U.S, Medium.com writes. In China, several hits, such as the micro-drama Wushuang, have recouped the production cost outlay in under a week, with total in-app “recharge” revenue passing RMB 10 M by day eight. When a single U.S. user ultimately spends US $20–50 to binge a full season, the margin crushes both Disney+’s annual ARPU and most match-three games, proving that micro-dramas aren’t just cheap; they are capital-efficient. Reuters wrote recently that vertical filming and distribution through social media apps mean microdramas can be made with small overhead costs. Budgets for such films range from between $28.000 (200.000 yuan) and $280.000 (2 million yuan), according to market researcher iResearch.

The pros of microdramas are numerous. For viewers, the short length and serialized nature make them highly accessible and convenient, fitting into fragmented daily routines. For creators, the lower cost of production compared to traditional TV allows for experimentation and rapid turnaround, while the addictive structure often guarantees high engagement. For platforms and investors, the monetization opportunities—from subscriptions and ads to in-app purchases—are vast. ReelShort has already rolled out small-town-revenge sagas, true-crime thrillers, campus romances, even an $800k “Game-of-Thrones-on-a-phone” epic.

However, there are also notable downsides. Critics point to the often formulaic and sensational nature of microdrama storytelling, which can sacrifice depth for speed. There are also concerns about the sustainability of audience engagement, as the novelty may wear off if quality does not keep pace with quantity. Additionally, regulatory challenges could hinder expansion, especially as microdrama apps often find themselves caught in the crossfire of debates around short-video platforms. The uncertainty surrounding TikTok’s future in the U.S. shows how quickly the landscape could shift.

In a recent video he posted on LinkedIn, Evan Shapiro urged people to stop calling the genre “ microdramas”. According to him “there is a real gold rush around microdramas in Hollywood and it is dangerous. The production practices are literally dangerous: they are spending almost no money to produce these things, they are often abusing and exploiting the labor both behind and in front of the camera. And in reality, they are not dramas, they are not real programming content - they are games, they are short, they get you addicted to them and then they charge you before they complete the whole story... All of these studios now rushing, like they always do, to cash in on this new movement - you can go back and look at the Quibi example of how it started, how it peaked and how it ended - pretty badly for everyone... If you want to start a new format, a new medium, connecting it to only one kind of genre is limiting. If this vertical trend of narrative storytelling is going to succeed it’s not going to be tied to just one genre and it’s not going to be tied only to scripted programming... The entire ecosystem, if it is going to succeed, won’t be behind a paywall and in app that you have to download in order to consume... If you look at Roomies - it is a really good example. It is a scripted comedy, on TikTok and on Instagram and was entirely sponsored by Built. Paid for by a brand, produced professionally, professionally written, professionally acted that is free. And that’s very likely when a lot of the vertical content will end up. Apps will be part of it... I wanna change the name of this medium - I call it Pocket Television.”

The evolution of microdramas reflects more than just a stylistic shift — it mirrors broader behavioral changes in streaming. According to Fabric data, smartphone drama preference shows distinct regional variations.

In UCAN, drama preference among smartphone viewers accounts for 53% of streaming, with the 25–34 demographic emerging with the highest preference. In APAC, where microdramas originated, dramas represent 47% of preference among mobile audiences, and unexpectedly, the most significant uptake comes from audiences over 55. LATAM records 47% preference, where younger audiences between 16-24 lead the trend. Meanwhile, in EMEA, dramas capture 45%, with the 25–34 segment once again at the forefront.

These data points confirm that microdramas are not confined to a single market or age group. Instead, they highlight how mobile-first habits are reshaping viewing preferences across generations and continents.

Mainstream streaming platforms have started integrating microdramas into their ecosystems to diversify their catalogs and capture new audiences. The strategy often begins on social media, where short teasers on TikTok or Instagram drive interest, before funneling users into apps for the full series.

ViX MicrO from TelevisaUnivision has opted for a completely free distribution model to maximize reach. Meanwhile, APAC pioneers like iQIYI and WeTV integrate microdramas into their premium VIP packages. These platforms typically release the first few episodes at no cost to spark engagement, then encourage upgrades to unlock the rest of the storyline.

While established services are adapting, dedicated platforms built exclusively for microdramas are leading the charge. Reel Short, for instance, already features +450 series in Mexico and +440 in Brazil. DramaBox and GoodShort have both surpassed one million downloads, while other challengers such as ShortMax, FlickReels, and RapidTV are building strong catalogs.

In Latin America, VYCO has emerged as a significant player. Beyond distribution, it invests in original productions with regional talent, tapping into local audiences and creating content that resonates with cultural nuances.

Looking ahead, the future of microdramas appears bright but competitive. As the global market heads toward the $20 billion mark by 2027, traditional media companies and streaming giants may increasingly enter the space, either by acquiring existing apps or by launching their own microdrama initiatives. The format’s ability to capture younger viewers, monetize effectively, and adapt across markets ensures that it will remain a force in global entertainment. Yet, its long-term success will depend on maintaining creative innovation, navigating regulatory hurdles, and proving that short can indeed be both sustainable and substantial.

Monetization strategies also distinguish the format from traditional subscriptions. Most platforms adopt a freemium model, where the first episodes are free and later episodes are locked behind in-app purchases with coins or credits. Others rely on advertising or hybrid models, allowing users to remove ads with a one-time payment per title or per month. This gamified approach monetizes attention in new ways, proving particularly effective with mobile-native audiences.

In China, the boom was almost immediate. The country’s well-established mobile entertainment ecosystem created fertile ground for microdramas to flourish. By 2023, microdrama apps were pulling in hundreds of millions of users, generating substantial revenues through subscription models, ad sales, and pay-per-episode options. According to a recent report by Media Partners Asia (MPA), the microdrama market outside China is projected to top $9 billion in the coming years while the global figure including China could exceed $20 billion, underlining the genre’s explosive growth potential. In details: revenues in China for micro-dramas have climbed from $0.5B in 2021 to $7B in 2024 and are expected to exceed $16.2B by 2030, with a 11.5% compound annual growth rate (CAGR).

By 2030, advertising will contribute 56% of revenues, with subscriptions at 39% and commerce at 5%. Outside of China, the global microdrama market generated $1.4B in 2024 and is forecast to reach $9.5B by 2030, with a 28.4% CAGR. In China, micro-dramas have become “mainstream,” with revenues set to exceed $9.4B in 2025, with more than 830 million viewers consuming microdramas. From this audience, nearly 60% pay or transact.

The Chinese microdrama market is also entering a new phase with the rise of premium micro-dramas, carrying budgets of $400.00 to 600.000 each, and with franchise potential. Artificial intelligence has already been integrated across the value chain, from personalized discovery, faster iteration, and genre testing, to branching storylines and viral loops.

Investment in microdramas is surging. Variety reported that global spending on microdramas exceeded $10 billion in 2024 and is forecast to rise sharply, with more than $20 billion projected within three years as Western and Asian companies compete for market share. This includes not only content production but also technological infrastructure, such as the recommendation algorithms that drive user engagement. According to Appfigures, ReelShort saw revenues of over $25 million in December 2024 alone, largely from in-app purchases and subscriptions, while DramaBox followed closely behind with double-digit monthly revenue growth. Appfigures counts 215 micro-drama apps on the U.S. stores, and May 2025 consumer spend topped US $100 million. Sensor Tower adds that the three largest apps now post ARPDAU figures that rival mid-tier casual games. These figures underscore the commercial viability of microdramas and their capacity to rival traditional streaming platforms in audience reach.

A season of sixty one-minute episodes typically costs from RMB 200–300 K (≈ US $27–41 K) shoot in China, or around $200K shoot in U.S, Medium.com writes. In China, several hits, such as the micro-drama Wushuang, have recouped the production cost outlay in under a week, with total in-app “recharge” revenue passing RMB 10 M by day eight. When a single U.S. user ultimately spends US $20–50 to binge a full season, the margin crushes both Disney+’s annual ARPU and most match-three games, proving that micro-dramas aren’t just cheap; they are capital-efficient. Reuters wrote recently that vertical filming and distribution through social media apps mean microdramas can be made with small overhead costs. Budgets for such films range from between $28.000 (200.000 yuan) and $280.000 (2 million yuan), according to market researcher iResearch.

The pros of microdramas are numerous. For viewers, the short length and serialized nature make them highly accessible and convenient, fitting into fragmented daily routines. For creators, the lower cost of production compared to traditional TV allows for experimentation and rapid turnaround, while the addictive structure often guarantees high engagement. For platforms and investors, the monetization opportunities—from subscriptions and ads to in-app purchases—are vast. ReelShort has already rolled out small-town-revenge sagas, true-crime thrillers, campus romances, even an $800k “Game-of-Thrones-on-a-phone” epic.

However, there are also notable downsides. Critics point to the often formulaic and sensational nature of microdrama storytelling, which can sacrifice depth for speed. There are also concerns about the sustainability of audience engagement, as the novelty may wear off if quality does not keep pace with quantity. Additionally, regulatory challenges could hinder expansion, especially as microdrama apps often find themselves caught in the crossfire of debates around short-video platforms. The uncertainty surrounding TikTok’s future in the U.S. shows how quickly the landscape could shift.

In a recent video he posted on LinkedIn, Evan Shapiro urged people to stop calling the genre “ microdramas”. According to him “there is a real gold rush around microdramas in Hollywood and it is dangerous. The production practices are literally dangerous: they are spending almost no money to produce these things, they are often abusing and exploiting the labor both behind and in front of the camera. And in reality, they are not dramas, they are not real programming content - they are games, they are short, they get you addicted to them and then they charge you before they complete the whole story... All of these studios now rushing, like they always do, to cash in on this new movement - you can go back and look at the Quibi example of how it started, how it peaked and how it ended - pretty badly for everyone... If you want to start a new format, a new medium, connecting it to only one kind of genre is limiting. If this vertical trend of narrative storytelling is going to succeed it’s not going to be tied to just one genre and it’s not going to be tied only to scripted programming... The entire ecosystem, if it is going to succeed, won’t be behind a paywall and in app that you have to download in order to consume... If you look at Roomies - it is a really good example. It is a scripted comedy, on TikTok and on Instagram and was entirely sponsored by Built. Paid for by a brand, produced professionally, professionally written, professionally acted that is free. And that’s very likely when a lot of the vertical content will end up. Apps will be part of it... I wanna change the name of this medium - I call it Pocket Television.”

The evolution of microdramas reflects more than just a stylistic shift — it mirrors broader behavioral changes in streaming. According to Fabric data, smartphone drama preference shows distinct regional variations.

In UCAN, drama preference among smartphone viewers accounts for 53% of streaming, with the 25–34 demographic emerging with the highest preference. In APAC, where microdramas originated, dramas represent 47% of preference among mobile audiences, and unexpectedly, the most significant uptake comes from audiences over 55. LATAM records 47% preference, where younger audiences between 16-24 lead the trend. Meanwhile, in EMEA, dramas capture 45%, with the 25–34 segment once again at the forefront.

These data points confirm that microdramas are not confined to a single market or age group. Instead, they highlight how mobile-first habits are reshaping viewing preferences across generations and continents.

Mainstream streaming platforms have started integrating microdramas into their ecosystems to diversify their catalogs and capture new audiences. The strategy often begins on social media, where short teasers on TikTok or Instagram drive interest, before funneling users into apps for the full series.

ViX MicrO from TelevisaUnivision has opted for a completely free distribution model to maximize reach. Meanwhile, APAC pioneers like iQIYI and WeTV integrate microdramas into their premium VIP packages. These platforms typically release the first few episodes at no cost to spark engagement, then encourage upgrades to unlock the rest of the storyline.

While established services are adapting, dedicated platforms built exclusively for microdramas are leading the charge. Reel Short, for instance, already features +450 series in Mexico and +440 in Brazil. DramaBox and GoodShort have both surpassed one million downloads, while other challengers such as ShortMax, FlickReels, and RapidTV are building strong catalogs.

In Latin America, VYCO has emerged as a significant player. Beyond distribution, it invests in original productions with regional talent, tapping into local audiences and creating content that resonates with cultural nuances.

Looking ahead, the future of microdramas appears bright but competitive. As the global market heads toward the $20 billion mark by 2027, traditional media companies and streaming giants may increasingly enter the space, either by acquiring existing apps or by launching their own microdrama initiatives. The format’s ability to capture younger viewers, monetize effectively, and adapt across markets ensures that it will remain a force in global entertainment. Yet, its long-term success will depend on maintaining creative innovation, navigating regulatory hurdles, and proving that short can indeed be both sustainable and substantial.